Sunday, December 29, 2024

Human knowledge map and AI

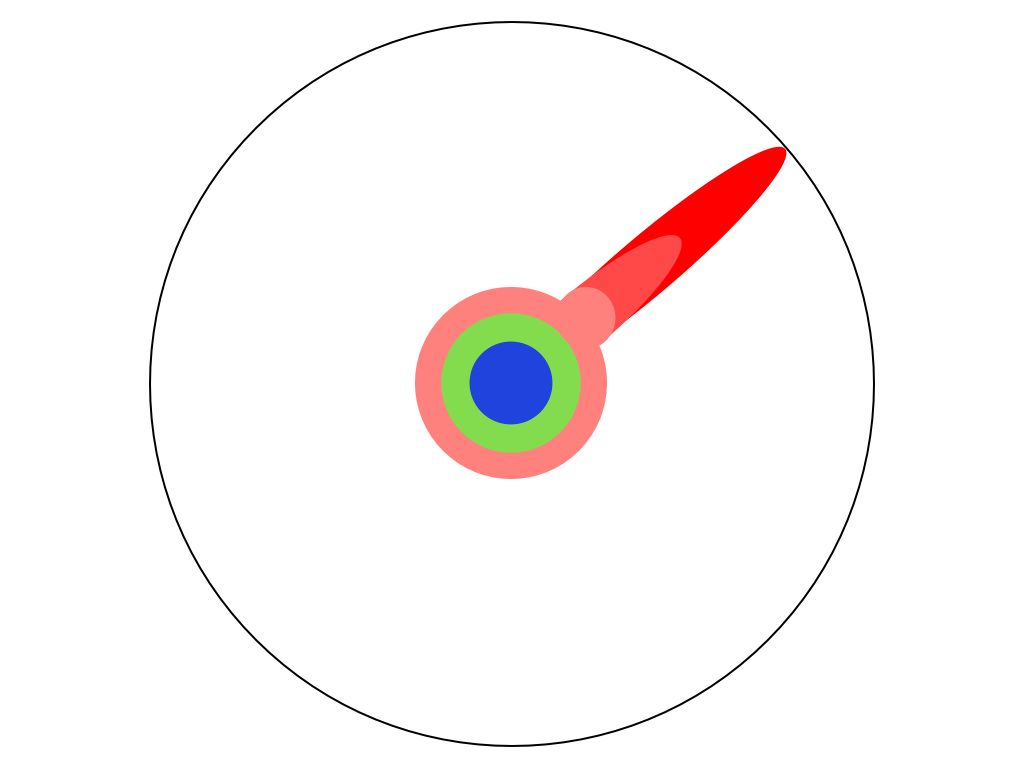

Some years ago, Matt Might, a US professor, published a graph with which he explains to his students what a Ph.D. means, by looking at where it lies on a graph of all human knowledge.The circles in the middle are the knowledge a student has picked up from elementary school to a bachelor's degree, and the red part is pushing knowledge to the edge of human knowledge during a Ph.D.

While useful to explain the point he wants to make, the graph has one major flaw: If you consider that the circular axis describes all fields of human knowledge, the knowledge you pick up at school or with any other education never makes a circle. No school curriculum covers the totality of human knowledge, and different students retain different amounts of knowledge, even if they visited the same class. If somebody actually could map his knowledge as it relates to all human knowledge, there would necessarily be peaks and valleys. Even outside a Ph.D. or job specialization, we know more about for example about the areas where our hobbies lie, and less of areas that don't interest us. A person with a bird watching hobby knows more than the average person about birds. But then he maybe isn't interested in sports at all, and knows less than average on that. That not only applies to knowledge, but also to skills, which are often related to knowledge. A car mechanic might be very skilled at fixing your car, but be bad at customer relations, or accounting.

Now if we look at large language model AI and map it on the same graph, we get a circle that is a lot smoother. AI aggregates the knowledge of many people, and thus the peaks and valleys cancel each other out, to some degree. But we also observe that the border is somewhat fuzzy: The AI lacks self-awareness of what it knows and what it doesn't know. The further you get away from the center, the more complex and specialized a question becomes, the more likely it becomes that the answer the AI gives is unreliable, up to the point of being completely hallucinated. But AI is really good at answering questions "everybody knows", which is helpful if you have a knowledge deficit is some area.

While companies have invested billions in AI, the business case for specialized AI software is a lot clearer than that for the more general large language model AIs. But I think that the awareness that people might have deficits in certain skills or knowledge, while AI is good at base level knowledge in general, might point us to a number of possible applications. I've seen in one video about AI a short demonstration of an AI software that helps managers give feedback in the context of a performance review to people who work for them. That won't help anybody who is already a great manager, but it could well provide a good baseline, where those managers who maybe got to their position for their technical skills and are a bit short on people skills receive help from that sort of software, and thus the people working for them get at least some basically helpful performance feedback.

I don't think that large language models will ever be able to work at the edges of human knowledge, to do Ph.D.-like research. But I do think they could be quite helpful at providing basic help and advice to set some sort of minimum standard. The AI knows "what everybody knows", and thus can be used to help people with skill deficits or gaps in their knowledge to bring them up to standard.